A Decade of Business Logic Lived in One Person's Head. I Had to Turn It Into a System.

I want to tell you about a project that genuinely scared me.

Not because it was high-profile or politically sensitive or anything dramatic like that. It scared me because I sat down, looked at the problem, and had absolutely no idea where to start. That almost never happens to me anymore, and when it does, it's humbling in a way that's hard to describe. You spend years building confidence in your craft and then something comes along and makes you feel like a junior again.

The ask seemed straightforward: design a CMS for product attributes. I've done that before. Should be a few weeks of discovery, some wireframes, a spec, done.

Then I actually looked at what existed.

What I walked into

The company has a product attribute system that works. It's worked for years. But like a lot of systems that grow organically over a long period, it has evolved well past the point where its original structure can support it cleanly.

The backbone is a set of large, interconnected spreadsheets. Thousands of product attributes covering everything from fit and fabrication to sleeve length, collar type, rise, pattern, season, country of origin, compliance labels, and countless nuances that have accumulated over time. This thing has layers. And it powers a lot of critical operations across the business.

One person in particular has become the connective tissue holding it all together. She knows which columns have invisible dependencies on other columns. She knows which vendor requests are routine and which ones will break things. She knows the exceptions to the exceptions. Every team in the company, merchandising, copywriting, vendors, ecommerce ops, internal reviewers, all of them rely on her expertise. And honestly, the fact that it all works as well as it does is a testament to how good she is at her job.

But the company has outgrown the tooling. What once made sense at a smaller scale is now a risk, not because anyone has done anything wrong, but because the business has evolved faster than the infrastructure supporting it. The organization knows this, which is exactly why I was brought in.

My job is to take everything that lives in spreadsheets and in her head and turn it into a system that can scale with the company. And sitting there in those first few days, listening to her explain layer after layer of interconnected logic that had evolved organically over a decade, I started to feel that familiar pit in my stomach. The one that says: this is way bigger than anyone thinks it is, including you.

I didn't know what to do

I need to be real about this part because I think people in product and design don't talk about it enough. I was lost. Not "oh this is a fun challenge" lost. Actually lost. The kind of lost where you close your laptop and sit there for a minute wondering if you're the right person for this.

The sheer volume of undocumented business logic was staggering. Every time I thought I had a handle on one area, she'd mention some exception or dependency that made me realize I'd only been looking at a corner of the thing. I was taking obsessive notes, recording every session, asking the dumbest possible questions to make sure I wasn't making assumptions. But even with all of that, I'd close out my notes at the end of the day and think: how am I ever going to synthesize all of this into something coherent? This felt like it could take months just to understand, let alone design.

There were nights where I seriously questioned whether I could pull it off. Not in a dramatic way. Just quietly, honestly. Sitting with the weight of knowing that a team was counting on me to make sense of something I couldn't yet make sense of myself. That's a lonely feeling. And I think anyone who's worked on genuinely complex problems knows exactly what I'm talking about, even if we rarely admit it out loud.

I've been doing this long enough to know that the worst thing you can do when you're overwhelmed is pretend you're not. So I sat with it for a bit. And then I tried something.

Using AI to make sense of the mess

I took all my transcripts, hours and hours of recorded conversations, and I fed them into AI. I want to be transparent about my motivation here: it wasn't some brilliant strategic move. I was drowning and I reached for the closest thing that might help.

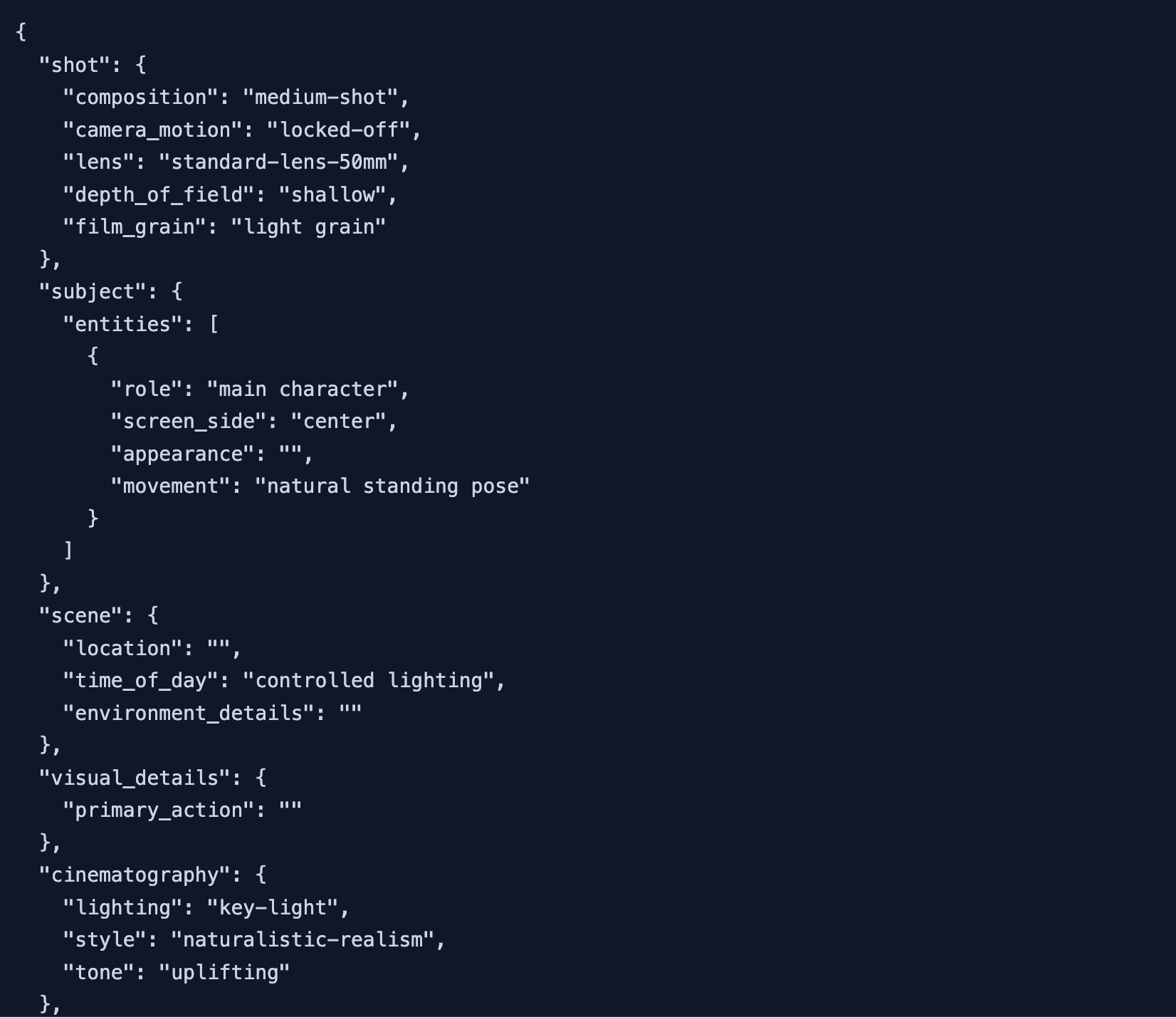

I asked it to pull out workflows, identify dependencies, map entity relationships, flag contradictions, surface edge cases, highlight areas where the logic was ambiguous. Basically, I treated it like a very fast, very tireless research assistant who could hold all of this information in its head at once. Something I physically could not do, and honestly was starting to feel embarrassed about.

What came back wasn't a finished product. It wasn't even close. But it was something I could react to. And that changed everything for me.

The hardest part of a problem like this isn't the complexity itself. It's the blankness. Staring at a mountain of unstructured information and not having a foothold. That blankness is where the self-doubt lives. AI gave me footholds. It gave me rough drafts of the system's logic that I could bring back to the team and say, "here's what I think is going on, tell me where I'm wrong."

And they did. They told me where I was wrong. And I revised. And I fed the revisions back in. And each cycle, the picture got clearer. Tribal knowledge started turning into documented logic. The thing that had been living across spreadsheets and inside one person's expertise started to have a formal shape.

I want to be clear: AI didn't design anything. It didn't make product decisions. It compressed a mountain of raw information into something my brain could actually work with. That's it. But that was enough to take me from "I have no idea how to do this" to "okay, I can see a path forward." I cannot overstate how much that shift mattered, not just for the project, but for my own confidence that I could actually deliver.

Building something people could actually touch

Once I had a solid understanding of the requirements, I didn't just make wireframes. I needed the team to be able to interact with the design, because this system is too complex for anyone to evaluate in the abstract.

So I built a high-fidelity, interactive prototype. Not a static mockup, but something that actually behaves like software. I used an AI coding agent to scaffold the UI, then spent a lot of time refining it myself. AI can generate structure fast, but it has no taste. It doesn't know which interactions matter, which error states are critical, which workflows need to feel effortless versus which ones should have friction by design. That's still the human job. And frankly, after feeling so unsteady during the discovery phase, the refinement work was where I found my footing again. That part I know how to do.

The prototype includes category hierarchies, attribute relationships, creation flows, review workflows, validation warnings, dependency mapping, display logic, versioning. The whole thing. You can click through it and it feels real.

The moment it clicked

The turning point wasn't when I finished the prototype. It was when the team saw it.

Something shifts when people can interact with an idea instead of just hearing about it. All those abstract conversations we'd been having suddenly became concrete. People started clicking through workflows and saying things like "wait, what happens if a vendor submits an attribute that conflicts with an existing one?" or "this doesn't account for the way we handle seasonal overrides." Edge cases that nobody had thought to mention before started pouring out. Not because people were holding back, but because they didn't fully understand their own process until they saw it reflected back to them.

The prototype became the shared language we'd been missing. It aligned engineering, product, and the stakeholders. And honestly, it was a moment of recognition for the person who's been holding everything together. Her knowledge isn't just living in her head anymore. It's visible, tangible, and forming the foundation of something the whole organization can build on. Watching her face when she saw it all laid out was one of the best moments of the entire project.

Where we are now

The prototype is done. Engineering can see exactly what needs to be built and how it should behave. What started as an organically grown spreadsheet ecosystem now has a clear path toward becoming a documented attribute model with centralized business logic, a scalable category hierarchy, structured vendor workflows, internal curation tools, clear validation rules, and most importantly, a system that won't depend on any single person's availability to function.

There's still a lot of work ahead. But the hard part, making the invisible visible, is done. The company now has a shared understanding of what this system actually is and a concrete blueprint for where it needs to go. That's not just a UX deliverable. That's the foundation for real organizational resilience.

What I've learned so far

I almost psyched myself out of this one. There were real moments of doubt, real nights of wondering if I'd taken on something beyond my ability. And I think that's worth saying because our industry loves to present work like this as a clean narrative. Smart person sees problem, applies framework, ships solution. It's never actually like that, at least not for me.

Here's what got me through it.

AI is genuinely powerful when you use it as a thinking partner instead of a replacement for thinking. The synthesis work that would have taken me weeks of staring at transcripts happened in days. When you're overwhelmed and losing confidence, that kind of acceleration isn't just a productivity gain. It's the difference between sinking and swimming.

When you're stuck, make something concrete. Anything. A rough diagram, a draft model, a bad first prototype. You cannot reason clearly about invisible systems. You need artifacts, things you can point at, argue about, and improve. The act of externalizing messy thinking is what makes it less messy.

Prototypes aren't just design deliverables. They're alignment tools. They end opinion battles. They surface hidden assumptions. They force clarity in a way that documents and presentations never will.

And you don't have to understand everything on day one. You just need a process that reveals the system to you layer by layer. Panic is what happens when you try to hold the whole thing in your head at once. Structure is what happens when you give yourself permission to not know yet and start building scaffolding instead.

This is the kind of work I care about most. Not the flashy stuff, not the pixel-perfect UI polish. The messy, structural, unglamorous work of turning chaos into something that holds. I was scared at the start, and I'm not too proud to say that. But having AI in my toolkit made the difference between this being a project that broke me and one I'm genuinely proud of.

Marco van Hylckama Vlieg

Builder shipping AI-native apps, games, and creative experiments.